We formed a circle in the sanctuary that Sunday. Haltingly, then with great emotion, the communion of saints shared stories of escape, of loss, of raw experience from the events of that week. At the end we held hands, locked together in common need, and prayed and prayed and prayed some more prior to approaching the altar for the sustenance and strength of the Lord in His Holy Meal. It was September 16, 2001, at St. Peter’s Lutheran Church in Brooklyn, New York.

Interview: Heather Choate Davis

Lutheran Forum interviewed artist, liturgist, musician, writer—and all around creative—Heather Choate Davis. In this conversation we discuss Heather’s background, inspiration for writing projects, her recent musical endeavors, and her hope for the future of the church. Learn more about Heather at her website: https://heatherchoatedavis.com/about/

In Defense of Lutheran Monasticism

Members of a Facebook group for those affiliated with confessional Lutheran churches were once asked whether monastic life should be supported; the responses were enlightening. There were a few who admitted to being Benedictine oblates or supporters while a sizable group was either in favor of monasticism or considered the matter an adiaphoron. On the other hand, another large group of respondents asserted that monasticism is wrong because Luther “was against it”; because we are supposed to “go forward and make disciples”; or because the Book of Concord says so. One person did not speak for or against it but merely said that there are “bigger fish to fry” than monasticism. In general, this group was divided on the issue of monasticism.

'Obscure and Senseless'? - Another Look at When Cajetan Met Luther

In 1517, the master general of the Dominican order, Giacomo de Vio, was made a cardinal. It was a fitting reward for a distinguished career in service of the Roman Church. The new cardinal was a well-respected theologian, and the foremost scholar of his age on the theology of Thomas Aquinas. He had taken over the role of master general after sixty years of weak leadership and made every effort to promote the reform of the order, recalling it to its central mission of preaching and teaching.

Book Review—Pearly Gates: Parables From The Final Threshold

Readers of Lutheran Forum may pick this book up because of their familiarity with the author, but will not necessarily find a familiar mode of writing. Pearly Gates is authored by former editor Sarah Hinlicky Wilson, and the reader can expect writing that tackles tough theological questions with wit and charm. But this book is not a series of LF essays. These are short stories—very short stories—that incisively communicate the meaning of life.

Book Review: The Holy Spirit and Christian Experience

Simeon Zahl’s new book, The Holy Spirit and Christian Experience, is a rarity, holding together two very different theses without coming apart at the seams. At the level of doctrinal content, the book is fairly traditional, advancing a version of early Reformation soteriology as hybridized from Melanchthon, Luther, and Augustine. From the perspective of theological method, however, the approach is innovative, proposing a theological application of that framework for interpreting emotion and the body termed “affect theory.” The glue connecting these elements is Zahl’s contention that questions about emotion and embodied experience are most naturally addressed within the doctrine of the Holy Spirit.

Christianity and Zombie Ants

Niccolò Machiavelli observed long ago that rulers need not actually be moral, or faithful to a principle that does not immediately reduce to their self-preservation; they need only create the appearance of such faithfulness. It is all about perception, a matter of optics. Now, that was half a millennium ago. In our own day, even that fig leaf appears to be superfluous. The push, on the part of the Republican senate majority led by Mitch McConnell, to have the president’s Supreme Court nominee confirmed and installed before the end of President Trump’s first term and the beginning of new Congress does away with even a shred of appearance. When, in this light, one considers the Republican protestations in the last year of President Obama’s tenure against Obama’s own nominee, it is all a fine specimen of what in Poland is called “primitive” morality: “I steal a cow: good! A cow stolen from me: bad!” Such apparently are the times. What matters is only self-preservation that need not bother any more covering its shameless immodesty with any appearance. It is all about power, unclothed and in your face.

A Lutheran Case For Reparations (Summer 2020)

Lutherans are fond of speaking of two kingdoms—or realms—in creation. In its simplest form, the doctrine of the two kingdoms teaches that God governs the right-hand realm by the gospel and the left-hand realm by the Law. All too often, though, because the right hand is the gospel’s realm, the left hand gets cast aside as having almost nothing to do with God. We might pay lip service to the left hand as being God’s realm too, but we have difficulty articulating what that means in any meaningful sense. The way this often plays out is that, in the right-hand realm, we settle issues on the basis of the teachings of Christ’s church, while, in the left-hand realm, we pivot to national myths.

Universalism And The Church: The Biblical-Christian Hope for Universal Salvation Revisited (Summer 2020)

The controversial belief among Christians that in the end all shall be saved has again become a subject of serious discussion. In 2019, David Bentley Hart published a book on the subject, That All Shall Be Saved: Heaven, Hell, and Universal Salvation.[1] The author is not a minor leaguer. Some have opined that he’s the smartest theologian on the planet, and as one not known for self-deprecation, he would probably agree. Hart is an Eastern Orthodox theologian, heir to a tradition rooted in the thought of Origen of Alexandria and Gregory of Nyssa, which kept the universalist vision alive as an option for Christians—in stark contrast to the Western tradition running from Augustine through Thomas Aquinas to Martin Luther, John Calvin, John Wesley, and Jonathan Edwards, who envisioned an eternal hell for those who deserved damnation by the God of justice for not believing in Christ and belonging to His church.

The Great Evasion: The Calling of the Laity

It is a great blessing to have a firm sense of purpose in life. The Lutheran teaching on vocation gives such purpose to life, not only to one’s work but also to one’s life in marriage and family, in citizenship, and in church. One’s purpose is to respond to God’s gracious call to employ one’s deepest interests and gifts in loving service to the neighbor in those “places of responsibility.”

What Can Evangelical Catholic Lutherans Offer to Today’s Wandering Souls?

In my last editorial, I offered a pathology of the malaise that seems to be afflicting evangelical catholic Lutheran witness, using the refrain “times have changed” to suggest that we evangelical catholics need to do a better job of advertising our vision for Lutheran faith and practice in this present milieu. The editorial was, I readily admit, something of a downer. Devoted to the task of diagnosing an ailing patient, I spent most of my time tracing the apparent deflation of our vision against the backdrop of two broader changes which have taken place in recent years; namely, the shift in internecine conflicts among Lutherans in North America from hot war to stalemate, and the transition of the modern ecumenical movement from a period of “revolutionary ecumenism” to a new era of “normal ecumenism.” Several readers opined that I was too grumpy and gloomy in the piece, and urged me that things are not as bad as I made them out to be. A few folks advised me to turn my attention to those small pockets of North American Lutheran life wherein evangelical catholicism appears (to them, at least) to be thriving. One letter writer even complained that I had unleashed a jeremiad upon unsuspecting Lutheran Forum readers still acclimating themselves to my editorial style. Perhaps.

A Papal Audience with His Holiness Pope Francis

Shortly after the commemorative medal for the 500th Anniversary of the Reformation, designed by The Reverend Doctor Frederick J Schumacher, STS, was produced by the American Lutheran Publicity Bureau, I was approached on several occasions to see what influence I might exert to get this medal directly into the hands of the Holy Father, Pope Francis. The medal was commissioned to commemorate the Pope’s visit to Lund Sweden to kick off the global 500th Anniversary celebration. The medal also recognized the Joint Declaration on the Doctrine of Justification, signed in 1999 by the Lutheran World Federation and the Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity. I thought the request was legitimate, and I was honored to take part in it.

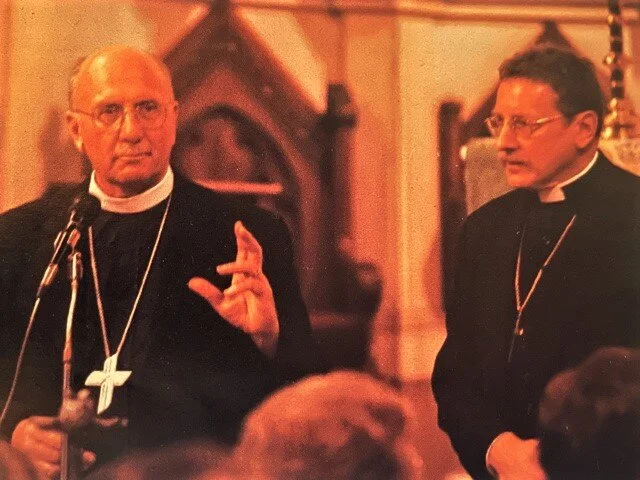

Leonard Klein: A Remembrance

I did not know Leonard Klein well. I met him first at the ALPB-sponsored Conference on Christian Sexuality in Kansas City in 2002. I bumped into him a time or two at various events in the subsequent years, and exchanged emails with him sporadically. At the 2002 meeting, he and I, along with Robert Benne and Paull Spring, had been appointed to a group tasked with drafting “A Pastoral Statement of Conviction and Concern” which was then discussed by the attendees and revised in light of the discussion. I do not recall just who contributed what to this statement, but two sentences in particular could be cited to summarize Leonard’s thinking. “Because we love the whole church,” the statement said, “many of us are facing a potential crisis of conscience regarding the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America. We earnestly desire to remain actively engaged in the life and mission of our church, but we observe that the ELCA is becoming schismatic and sectarian.” (It is perhaps worth noting that I am the only one of the group of four who remains in the ELCA today.)

What Matters

It has been over 40 years since I was pastor here in Täbingen from 1972 to 1974. And now you have asked me to speak to you about what keeps faith alive, what nourishes it, so that it does not dissipate and die away, speechless, mute. How is it that faith that once was vibrant and fervent can become dull and silent? And how does it happen that those who once were joyful in faith, and full of love and gratitude, can become apathetic or cynical, despondent or indifferent, listless and lethargic? Their expectations of God have flagged, they are without hope, their love has grown cold, their faith is lost, dead. There can be many reasons for the death of faith, for the loss of the unconditional trust and confidence that faith is. When faith is lost, spiritual attack (Anfechtung)—that tremendous challenge to faith—has triumphed. In such times, the only thing that can stand up to this attack, that can resist it, is that which gives life to faith, keeps it alive, and keeps creating it anew as it overcomes the attack.

It's Time to Turn and Face the Flag

No one grows up in America without some relationship to the flag. As a girl, I went to a private school where we all lined up by grade in neat rows for the Pledge of Allegiance. In sixth grade, I was part of the team that raised, lowered, and folded the flag gingerly, mindful to the point of anxiety about any part of it touching the ground. But my feeling regarding the flag had nothing to do with my feeling about God. It’s not supposed to. This essential truth is woven into the fabric of the promise of being an American: you don’t have to believe in God to be a good citizen. And being Christian does not make you a better or more important American than anyone else.

The Philosophy of Bolshevism, Fascism, and Hitlerism, Parts I & II

Born in 1888 in the district of Senica, Samuel Štefan Osuský lived until 1975. He studied in the Lutheran Lýceum in Bratislava and at the theological seminary of the same church; he then studied in Germany at Erlangen and Jena from 1914 to 1916; he was awarded the PhD by the philosophy faculty of Charles University in Prague in 1922. He began to serve as a vicar in 1911, then as a pastor during the war years until 1919. He became an adjunct professor on the staff of the Lutheran seminary in Bratislava in 1919, a regular professor in 1920, and a full professor in 1933. He taught at the seminary until the Communist purge of the faculty in 1951, when he was prematurely retired. Osuský was elected one of two bishops of the Slovak Lutheran Church in 1933 and served in that capacity until 1946. He was imprisoned during the years of the First Slovak Republic for his opposition to the wartime fascist government, whose inhumane treatment of the Jews he protested alongside the leadership of his church in a public letter in 1942 during the time of the first deportation of Slovak Jews to Auschwitz.[1] Apart from responding to crises, Osuský’s many-sided academic work was focused on gathering philosophical, historical, and scientific resources for education in support of faith in the modern world; he conceived of this theological work as “a service to the nation,” lifting up the contributions of Slovak Lutherans to the formation of the first Czechoslovak Republic and its renewal after 1945. This work put him into conflict with the political Catholicism of the 1930s and 1940s as well as with the Stalinists who captured the government in 1948.

A Leap In The Dark (LF Summer 2019)

Karl Barth gave a nod to his publisher and close friend, Arthur Frey, in the preface to Church Dogmatics III/4. In 1937, and just before he completed volume I/2, the Nazis censored Barth from publishing his work with presses located on German soil. Forced to end his longstanding relationship with Christian Kaiser Verlag in Munich, Barth switched over to the Swiss press Evangelische Buchhandlung (later Evangelischer Verlag), which Frey piloted from before the war until his death in 1955.

Barth ended up publishing with the Swiss firm for the rest of his life, partnering with Frey on many of the remaining volumes of the Church Dogmatics (up to IV/2) and on numerous shorter books on various themes in Christian theology. “I do not think that there are many publishers,” Barth remarks in 1951, reflecting upon his years working with Frey, “who could have brought with them the understanding and the love, but also the skill and width of vision, which were necessary for something which more than once perhaps looked like a leap in the dark.”

Evangelical Hope Against Cultural Anxiety

“For I know the plans I have for you, declares the Lord, plans for welfare and not for evil, to give you a future and a hope.”

—Jeremiah 29:11

The seductive siren’s call of societal decline is a preoccupation of conservative Americans, and so it is also a preoccupation of conservative American Lutherans. While the verse from Jeremiah above has been misapplied countless times to more trivial matters—and matters having nothing to do with the verse’s context at all—it is pertinent in an article that hopes to give hope from within Babylon. American Lutheran church bodies are in decline, and the Lutheran Church–Missouri Synod is no stranger to this phenomenon. As of this issue’s publication, we are just a year away from the results of another election for synod president, and just over a year away from another synod convention. No matter who you may support as synod president, the question at this point should be: what will be the hope-filled vision for the future of the LCMS?