This Character Counts

by Matthew E. Borrasso

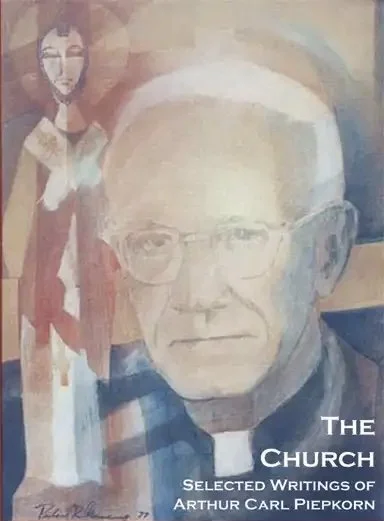

Editor’s Note: Throughout 2024 Lutheran Forum online will be featuring essays by mid-20th century theologians from the Lutheran Church—Missouri Synod. The essays will also be accompanied by an editorial length reflection from a contemporary theologian in the LCMS. This is the first in that series.

The following essay has been transcribed from a handwritten manuscript in the archives at Concordia Historical Institute. Thanks to Concordia Historical Institute for providing the author with the essay. Any perceived errors are likely the fault of the transcriber and not the author.

Does character count? Whether I was in a specifically Lutheran, broadly Christian, unashamedly public school the answer to that question was the same: yes, character counts. And yet, it seems today that in the public square, and dare I say in the ecclesiastical one too, the answer has changed. Character may count to a point, but results matter more. Ends, it would appear, justify the means. Whatever is the most politically or ecclesiastically shrewd maneuver to achieve the desired outcome is the move to make. Does character count? Not when truth, or what is right, is on the line. When the stakes are at their highest, character can be at its lowest. At least, that seems to be true for some.

Perhaps it is the echoes of my Lutheran grade school or public high school, but the present reality does not sit right with me. I am one who believes that character counts and that ends do not justify means. I believe that when the stakes are at their highest character must match it. I also believe, perhaps naively, that the choice between truth and brotherhood is a false one. I believe these things, in part, because I have seen them to be possible. I have seen that when truth was on the line, the truth about the scriptures and the radical Gospel they proclaim, character was at its highest. I have seen someone choose both truth and brother, someone who would not be forced into false choices or equivalencies. I have seen it in the person and work of Martin Hans Franzmann.

If Martin Franzmann is remembered today at all it is likely because of his hymnody. To be fair, his hymnody is reason enough to remember him. That does not mean, however, that this should be the case. He was a poet, but he was more than a poet. He was a theologian, exegete, professor, ecumenist, and servant of the church. He once said that his wife Alice was the “lady who (saving all their lovely reverences) has made all other ladies seem a bit pale by comparison.”[1] For me, Martin Hans Franzmann is the Lutheran theologian, who, saving all their lovely reverences, has made all other Lutheran theologians, especially those named Martin, seem a bit pale by comparison. The others pale not simply because of his artful use of language or penetrating insights into the biblical text but because he was the rare breed of theologian who actually embodied what he believed. The others pale not simply because he was known for being irenic and kind but because he actually was irenic and kind in the most difficult of circumstances. The others pale because perhaps no other is as needed in our present moment as much as he was needed in his own.

The essay that follows gives a glimpse of the man I have seen. Although it has never been published, the essay was delivered in 1972 to mark the 125th Anniversary of The Lutheran Church—Missouri Synod. Specifically where and when that essay was delivered remains elusive. The broader context of the Missouri Synod, however, is well known. The essay was delivered near the height of the controversy that marks mid-twentieth century Lutheran history. The stakes, as it were, seemed to be at their highest as the nature and authority of the scriptures, Lutheran theology, and the gospel itself, were being debated. Institutions and families were pitted against each other in an effort to preserve doctrine thought to be life. While theology is at the heart of the struggle, so too are questions about how brother and sister should treat each other. There was never a question in Franzmann’s mind: brothers are brothers, truth is truth, and they are all held together in Christ and his radical Gospel.

In this essay Franzmann is unflinching in his confession of the truth and uncompromising in his stance that “unfairness toward seriously searching men is not a virtue.”[2] As you read his words you will see what I have seen, someone whose character is not compromised when the stakes are at their highest, someone who chooses both truth and brother, someone who will not let the machinations of the church militant, the very ones he fell victim to a few years later, rule his heart and action.[3] Ultimately this essay does what all of his works do, expose the darkest parts of ourselves in comparison to the light of Christ that shines through him. That is why, I would contend, a Franzmann revival is needed in our time. It is not simply that he was artful, poetic, kind, or irenic, it is that in being those things he shows us a better way to embody our theology, and what is more, he shows us that it can be done when things matter most—he shows us just how much character continues to count.

Lutheran Church—Missouri Synod

125th Anniversary, 1972

by Martin Hans Franzmann

The 125th anniversary of the Lutheran Church—Missouri Synod promises to be a sober one. As in previous anniversaries, the atmosphere is scented not only with roses and lavender but with the earthier and more acrid smells given off by the machinery of the church militant in motion. There is nothing too unusual or disturbing about that. The Church has always stood and endured because it is stronger than its strongest human link and is never so weak as its weakest human link. All we have ever had to rejoice in is the enduring and stable mercy of God: we endure and conquer only because the Son of the Living God has said, “I will build my church.”

But there is one feature in the Missouri Synod today which is really disturbing and sobering; we have discovered, or are discovering, that what we love most troubles us most—an experience that most loving and beloved spouses could certify as a universally human one. We are troubled about the sacred Scriptures, the word of God written. We could write as a caption over our history the words of Jeremiah:

Thy words were found, and I ate them,

and thy words became to me a joy

and the delight of my heart;

for I am called by thy name,

O Lord, God of hosts. (Jer. 15:16)

God’s words “were found”; Jeremiah’s language is intentionally reserved and mysterious. And we must describe our experience with the Word in similar language. How or why it should have happened that there grew and burgeoned in our midst the “radical Gospel” of the Reformation, no history of our writing can rightly explain; the mercy of God in which we rejoice remains the unplumbed mystery of His love for us, the incalculable moving wind of His Spirit among us. We can but record the joy and delight of heart that His words have unfailingly been to us. We can but gratefully rejoice in the divine mercy which opened up for us anew the Reformation re-discovery of the Gospel of God “concerning his son, who was descended from David according to the flesh and designated Son of God in power according to the Spirit of holiness by his resurrection from the dead, Jesus Christ, our Lord.” (Rom. 1:3–4).

Why, then, are we troubled? Need we be troubled? Let us look together at the radical Gospel of the Reformation and attempt, for love’s sake, that most difficult of human feats, a diagnosis of our own disease – or at least a preliminary and partial diagnosis; the whole operation would require more wisdom and more time than most of us have at our command. There seem to be especially two points which call for consideration and reflection. One is a matter of substance, the other a matter of method. The question of substance is posed by the servant form of the Gospel, its historical and incarnational character; the question of method has to do with the nature and the limitations of the scholarly device called an “hypothesis.”

I. The Question of Substance: The Radical Gospel

Our fathers of the Lutheran Reformation discovered, or re-discovered, the unity of the Bible in what may be termed the “radical Gospel.” To this radical Gospel, they maintained, everything in the Bible is, in one way or another (as Law or Gospel) related; everything in the Bible serves, or subserves, to proclaim that God, to whom man can find no way, has in His Son Jesus Christ opened up a way that man may and must go. This Gospel is radical in three respects: (1) It deals with radical seriousness with the wrath of God revealed from heaven against all ungodliness and unrighteousness of men; it will not suppress the truth even in its most uncomfortable and intractable aspects, as, e.g., in the doctrine of original sin (CA II). (2) It deals with radical seriousness with the complete gratuity of the love of God who loved and saved us when we loved Him not and seeks us even when we rebel against Him and flee from him. (3) It deals with radical seriousness with the love of God which takes us as we are but will not leave us as we are; we come before Him as beggars who hunger and thirst for righteousness, and we receive from Him the royalty that befits God’s sons and the righteousness which enables us to live before Him as the merciful and pure in heart.

The radical Gospel of the Reformation is, then, radical in its recognition of the verdict of the law and of the guilt of men, in its appreciation of the grace of God as pure giving into beggars’ hands, and in its assessment of God’s grace as the transforming and creative power which enables us “to live sober, upright, and godly lives in this world.” In all three of these aspects the radical Gospel, as it were, walk on the ground. The wrath of God is revealed, in irresistible majesty, “from heaven” (Rom. 1:18); but it does its terrifying work on earth, among men, in history, in the agony of man’s unleashed and rampant sensuality, in the degrading horror of sexual perversion, in the dog-eat-dog rebelliousness which rends all social fabrics (Rom. 1:24–32) and creates an anticipatory hell on earth. The grace of God, again, is no general divine beneficence floating vaguely over the world and history; God enters history, chooses and creates a nation there, and moves with this word in grace and judgment through that history. The history of His grace culminates in the coming into the world of the Word made flesh, in the history of a life lived in first-century Palestine, in the history of the One executed under Pontius Pilate and raised again on the third day (a calendar event!). The God who gave His Son for our redemption and opened up His glorious future from our futureless and inglorious race in this grace trains us “to live sober, upright, and goldy lives in this world” (Titus 2:12) as we await the final fruition of our hope. We remain in the world and in history, waiting and working there within the orders which God has established in order to preserve us from a chaos of our own creation. We are created through the gospel, to be the salting salt of the earth and the shining and witnessing light of the world.

This “earthiness” of the Gospel is essential to it and is not the least of its glories. If we seek to evade it, we are the losers by that evasion. We cannot escape it even if we would, least of all in the Bible, unless we want to make the hopeless attempt of spinning out on our own something more “spiritual” (less tied to humanity and history) than the Gospel as contained in this collection of ancient documents that has the earthy smell of history on all its pages—from the picture of Adam cowering in the bushes at the beginning to the oriental jeweled splendor of the New Jerusalem at the end, with the homely picture of a messiah who spits on the ground to make clay for the healing of blind eyes in the middle.

When we look at the outward aspects of the word of God written, at the nature and history of the Bible as a book, we find them to be in keeping with the earthy character of the Gospel which the Good Book contains. The Bible is written in human languages, with their human histories and mutations. Even within so homogeneous a body of literature as the Old Testament there are linguistic mutations to be observed, and New Testament Greek bears the impress of its age upon it. The emphatic word-order employed by the New English Bible in translating 2 Peter 1:21 is true to the original, and what the words say holds of the writers of both Testaments: “men they were, but, impelled by the Holy Spirit, they spoke the words of God.”

The men impelled by the Holy Spirit spoke and wrote in their natural language; and they employed the literary forms of their place and their day. One scholar has spoken of the use which the Old Testament prophets made of all manner of current literary types, “almost as though everything that could be used for compelling utterances was looked upon as grist to the prophetic mill.” The dirge of Amos 5:1–2 and the song of Isaiah 5:1–2 are good examples. The authors of the New Testament letters employ current epistolary forms, quote secular writers and current proverbs, and were illustrations drawn from the life round about them. There are striking exceptions, of course; our Gospels, as a literary type have, at most, distant cousins in the contemporary Judaic and Greek world but no blood brothers – the Life that was the life of men as proclaimed by the Evangelists was a life without parallels and called for a new form.

The transmission of the Word did not differ markedly from the transmission of other ancient words. The oral word was held fast in the retentive oriental memories of disciples and friends and passed on to faithful men before it was written down. Once written, the Word was copied by scribes who made the same sort of mistakes as other copyists made. It will not do, of course, to lose sight here of the Holy Spirit as the great Remembrancer (John 14:26), or of what has been called the “singular will to transmission” in Israel which ensured the continuous life and influence of her sacred writings (in contrast to other Near Eastern texts) or of the fact that the New Testament text has been preserved by a number and a variety of witnesses quite unparalleled in antiquity. But this should not obscure the fact that the transmission of the written Word has a history quite as earthy as that of the Incarnate Word.

The story of the gathering of the sacred books into one authoritative collection of books, the story of the canon, is one that moves on the ground also. The canon imposed itself upon the Church in an undramatic manner, not by way of any spectacular miracle, not by the pronouncement, even, of an impressive body of experts, nor by way of authoritative conciliar decrees; the down-to-earth “profitableness” of inspired writings, their utility in the life of the worshiping and functioning Church, established the authority of the sacred writings. Historically, books came to be canonical by way of being read in the churches.

What follows? It would seem to follow from the on-the-ground, down-to-earth character of the radical Gospel and its course through history that we should be wary of ruling out, at the outset, any possibility as to where or how the Holy Spirit may go. Certainly we dare not declare out-of-bounds any linguistic (there was a time when men argued, in the name of orthodoxy, that the Holy Spirit could not inspire such grammatical infelicities as an anacoluthon) or stylistic forms as not within the choice of the Holy Spirit in order to get said what He wants said. We cannot dictate how, for example, the Holy Spirit should write history; He is free to write it in any way He chooses, employing what men He chooses, leading them to employ what sources and what styles He chooses. We must allow Him to do His work inerrantly and effectively in His way. We dare not deduce anything about His work, saying, “Because He is the Holy Spirit, He cannot go this way or that way; He must necessarily go this way.” We must allow him to go ways that seem, to us, precarious. We cannot deduce or prescribe; we can only observe. We are witnesses, no more, thank God; and no less, and again, thank God. Are we offended at the lowliness of what we observe? We do well to recall Jesus’ words to the Baptist when he was tempted to be offended at the lowliness of Jesus and asked, “Are you He who is to come?” Jesus’ answer culminated in the warning: “Blessed is he who takes no offence at me.”

Perhaps we shall do well to pray:

Made lowly wise, we pray no more

For miracle and sign;

Anoint our eyes to see within

The common, the divine.

We shall have an answer to our prayer: the miracle of the divinum of Scripture will burst upon us just when we do not evade the character of Scripture as “common,” as “the swaddling clothes of Christ,” to use Luther’s phrase.

But what of the point where observation ends, where the questing mind of pious man seeks to go beyond the observable facts in order to inquire concerning probabilities in order to throw light on obscurities that remain when careful observation has done its owr? This takes us to our second point.

II. A Question of Method: The Nature and Limits of the Hypothesis

The questing mind of even pious men being what it is, and the history of many hypotheses in biblical studies being what it is, one is tempted to render a quick and easy verdict: hypotheses are of the devil. But the quick and easy answers are not always the best answers, and unfairness toward seriously searching men is not a virtue. We shall do better to inquire seriously into the nature of an hypothesis, its value and limitations. A dictionary defines “hypothesis” as “an unproved theory, proposition, etc., tentatively accepted to explain certain facts or (working hypothesis) to provide a basis for further investigation, argument, etc.” The hypothesis is an attempt, admittedly tentative, to get a glimpse of the whole when only a part is known, by conjecturing the whole from the part that is known. It resembles the process we employ in drawing lines between numbered points in a picture-puzzle in order to get the whole picture—with the difference, of course that not all the points are as yet marked and known points are not conveniently numbered. Detectives employ hypothesis when they attempt to reconstruct the story of a crime on the basis of incompletely known facts. It is the detective-element, one supposes, that makes hypothesis-construction such a fascinating business.

Obviously, the hypothesis has certain value. The construction of an hypothesis ensures, or should ensure, a careful examination of all the known facts; and it clarifies the situation by giving us at least a tentative view of the whole, from which the significance of each part and the relationship of the parts to one another can be more adequately judged. There have been cases enough where a carefully constructed hypothesis has been confirmed by the discovery of new facts, just as there have been cases where fresh discoveries have ruined beautiful hypotheses. In the scientific field, the hypothesis gives direction and purpose to experiment, by which the hypothesis itself is checked. In matters of history and ancient documents, of course, experiment is impossible and the value of the hypothesis is less.

The hypothesis, just as obviously, has its limitations. It is by definition tentative; but that obvious fact is easy forgotten, especially when the hypothesis is elaborated and hypothesis is built upon hypothesis. The resultant profusion of hypothetical facts creates an illusion of plenty amid actual scarcity and can blind men to the obvious truth that hypothesis is not fact and cannot itself count and weigh as fact.

Moreover, the hypothesis tends to progress by means of rational and regular steps, while lift itself often moves irrationally and irregularly. An hypothesis attracts and convinces by the very neatness of its regularity and can blind us to the fact that its neatness may be its greatest weakness. This is especially the case where we are forced to work with a considerable number of unknowns and our skill in manipulating the unknowns flatters us into believing that they are knowns.

The most dangerous factor in any use of the hypothesis is the tendency to read one’s own preconceptions and presuppositions into it, often unconsciously and unintentionally. We may read twentieth-century conceptions into first century (how often Peter and John and Paul appear as University theologians instead of the working and praying apostles that they were!) or Western ideas into an Eastern cultural setting. We may tend to operate with a conception of history which has room only or an idiot succession of causes and effects—and no room for the living God and His creative Spirit. We may impoverish the range of possibilities to be reckoned with in dealing with a biblical document by limiting the possibilities to our prosaic and rationalist frames of reference and so miss the aim of all interpretation—that the reader be finally left alone with the text in all its marvelous possibilities.

None of these aberration is inevitable. But we need to keep them in mind, if only to preserve our nonchalance over against any untried hypothesis and our own sense of balanced reserve even over against any hypothesis, however widely accepted. I remember a three-year-old boy’s remark after hearing all the arguments as to whether a piece of linoleum would fit into a certain space in the neighbor’s kitchen: “Let’s lay the fool thing down and see if it fits.” The hypothesis calls for neither adoration nor anathema. Let us just lay the fool thing down and see if it fits.

Matthew E. Borrasso, PhD, is pastor of Trinity Lutheran Church in Lexington Park, MD.

Notes

[1] Martin Hans Franzmann, “Of a Man and Four Rivers,” British Lutheran 14, no. 8 (October 1969): 6.

[2] Martin Hans Franzmann, “Lutheran Church—Missouri Synod, 125th Anniversary, 1972,” 9.

[3] For more information on Franzmann’s life, including an annotated bibliography of his work, see: Matthew E. Borrasso, The Art of Exegesis: An Analysis of the Life and Work of Martin Hans Franzmann (Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock, 2019).