This Character Counts

Does character count? Whether I was in a specifically Lutheran, broadly Christian, unashamedly public school the answer to that question was the same: yes, character counts. And yet, it seems today that in the public square, and dare I say in the ecclesiastical one too, the answer has changed. Character may count to a point, but results matter more. Ends, it would appear, justify the means. Whatever is the most politically or ecclesiastically shrewd maneuver to achieve the desired outcome is the move to make. Does character count? Not when truth, or what is right, is on the line. When the stakes are at their highest, character can be at its lowest. At least, that seems to be true for some.

Music Review: Requiem in the City

“No matter who you are or what you believe, if you’re in a big city and pass by a cathedral, the odds are you’ll go inside. There, you’ll be met with a sense of peace, of awe, of something bigger. The beauty might even move you to light a candle. And so our story begins.” —Heather Choate Davis (Sophia Streams)

Love and the Incarnation

That love stands at the center of the Christian imagination is a statement of the obvious. It is impossible to speak of God without rather soon turning to love that gives all our God-talk its center and texture. Likewise, it is impossible to speak of humanity without summoning love to show us what it is that endows our being with ultimate meaning, or what, when present by its conspicuous absence, makes us into clanging cymbals. The Bible addresses itself to both of these: the overabundant love of God and the rather halting and often wanting human love.

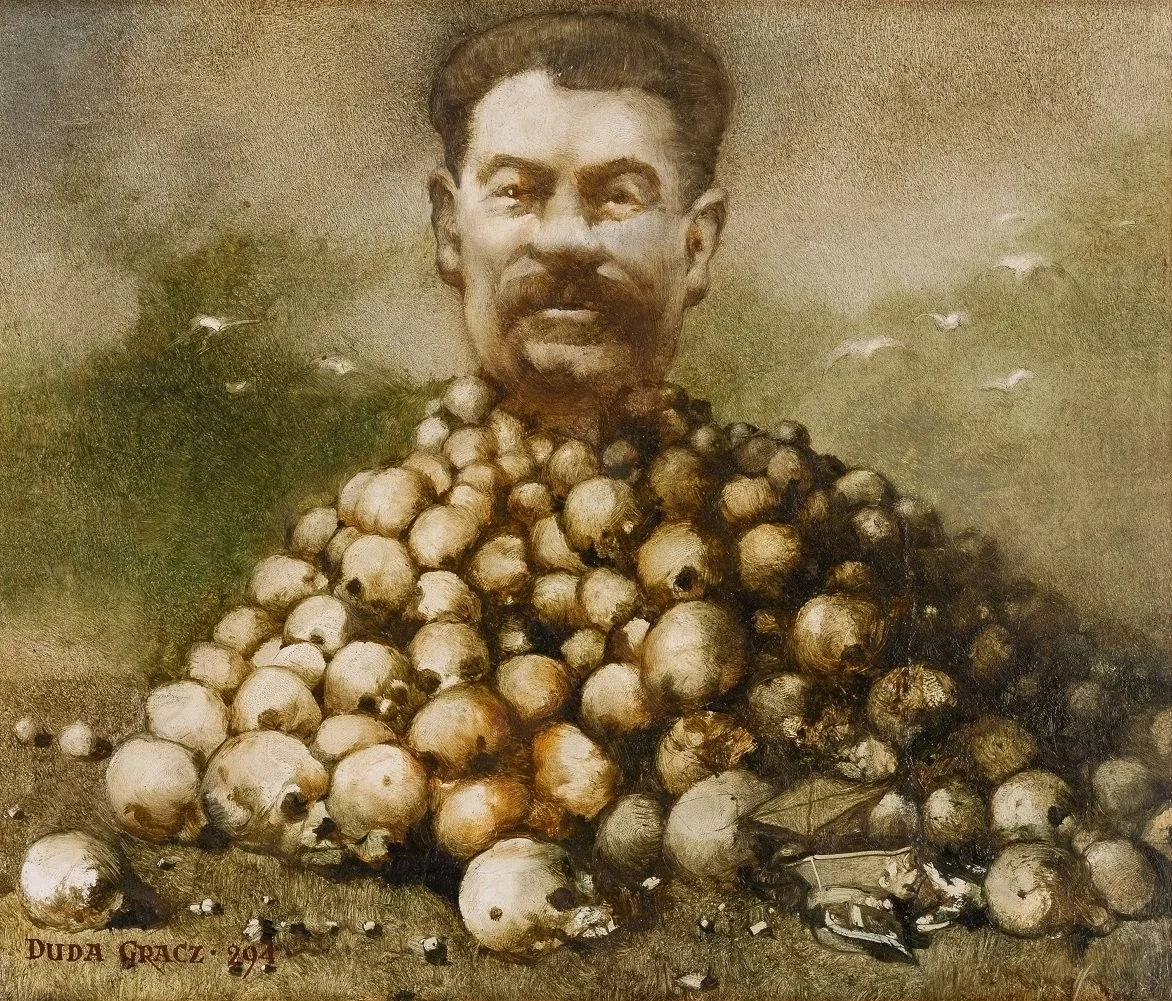

The War on Ukraine: Two Thoughts

Covid-era travel has been both precarious and full of unexpected opportunities. Jumping at one of those last fall, I purchased my ticket to travel to Poland in time for my mother’s 70th birthday in March 2022. Of course, once the time came for me to fly out of Alabama, the world had changed. And it wasn’t a matter of lockdowns, masking, or other pandemic-related restrictions. It was a matter of war—all of a sudden raging rather discomfortingly close to my family home.

Robert Jenson’s Catholic Lutheranism

Evangelical catholicism in American Lutheranism appears to be in decline. In a recent Lutheran Forum editorial, R. David Nelson admits he was tempted to profile the movement by invoking the image of an autopsy. He chose instead to offer an account of a “pathology.” Whatever image one might summon, there is no question that it’s a movement in crisis. There is an institutional explanation for the malaise of evangelical catholic identity: Lutheran unity in the United States appears to be an impossible dream. But there are also underlying theological reasons for the crisis. To trace these reasons, I’ll take Robert Jenson, his catholic Lutheranism, and its reception as a case study.

Robert Jenson On The Ascension

Anyone who enjoyed conversations with Robert Jenson feels the inadequacy of writing a critique of even a small portion of his thought. In living conversation, I found Jens always about three steps ahead of me, and only upon reflection—and that sometimes long delayed—did I realize where he was going. Now that he is gone from us, we have only his written words, which perforce lack the dialectical nimbleness of ongoing conversation; they are simply marks on a page.

The Altar Is Your Star

A Christmas meditation from Berthold Von Schenk (1895–1974).

A Sermon for the Fourth Sunday in Advent

Lutherans don’t really know what to do with Mary, the mother of our Lord. I think most of us want to like her but there’s an anti-Roman Catholic streak in Lutheranism that complicates this desire. Many Lutherans—especially in this part of the world—are former Roman Catholics and they recall a Marian devotion that dominated so much of their religious upbringing. There are other Lutherans who have no Roman Catholic background but nevertheless were reared on some old fashioned anti-Roman catechesis. Those who don’t fall in either category are probably indifferent towards Mary.

Music Review: Jesus, Coming Light

Jesus, Coming Light is the latest offering from 1517 Music. 1517 is a publishing and media house founded and led mostly by Lutherans that “create and distribute theological and apologetic resources anchored in the central message of the Bible: that Christ died for sinners and rose for their justification.”

The Church Of All Ages In Luther’s Lectures On Genesis

One of the more remarkable features of Luther’s Lectures on Genesis is the way in which he relates the biblical texts to the church of all times and places. In what follows I will highlight this point with some key moments in Luther’s treatment of four individuals from the book of Genesis—Abel, Noah, Abraham, and Jacob—when he speaks of their significance for the church of all ages. I conclude with what these examples indicate about Luther’s approach to the Old Testament as Christian Scripture.

Interview: Sarah Hinlicky Wilson

Lutheran Forum interviewed our former editor, Sarah Hinlicky Wilson, in a wide ranging conversation that covers Sarah’s work in pastoring, writing, publishing, podcasting, and ecumenical research. The body of the interview text includes web links so you may learn more about Sarah’s work.

The Dangers of Being “Churched” and “Worshipped”

Just when I thought things could get no worse than the service-sector-type categorizations of “churched” and “unchurched” populations, what arrived on the scene but “pre-churched” and “post-churched” (and lest we forget, “de-churched”)—all rather puzzling terminology to consider even before the COVID-19 pandemic when steady estimates for a while already held that only one-third of church members, or less, actively “practiced” their faith on a regular basis. It might just be my lack of understanding, but doesn’t that render the majority of the “churched” actually “unchurched,” let alone whatever other blurring gets introduced by those “attending” a streamed worship service on their couch? Is the goal of Christianity to get people to attend services and affiliate with a congregation or enter into the entity the Apostles’ Creed defines as “the holy catholic Church, the communion of saints,” or both? Soren Kierkegaard was on to something when he prayed, “Let us never forget that Christianity is a whole course of life.”